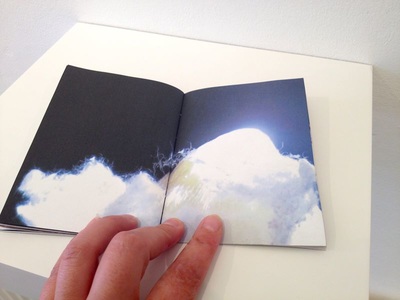

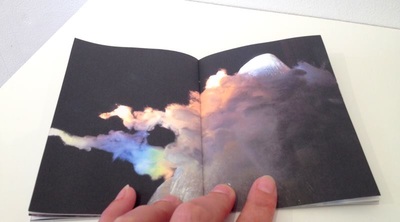

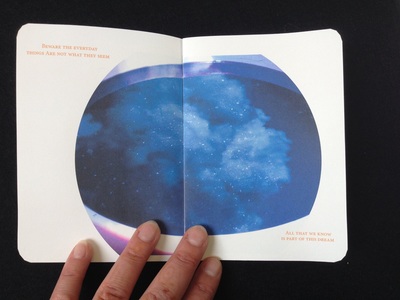

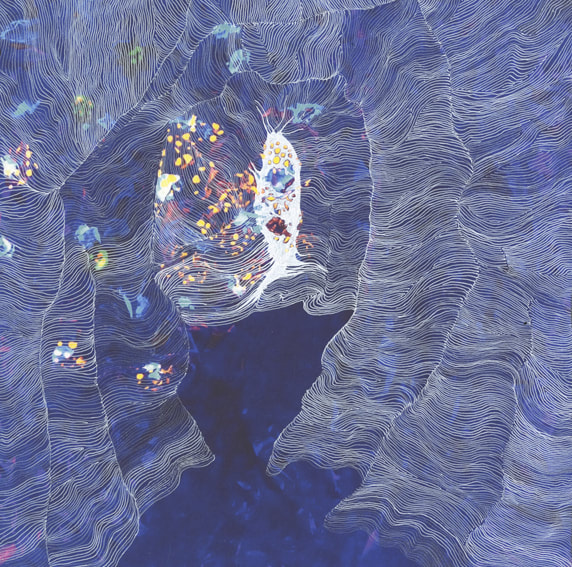

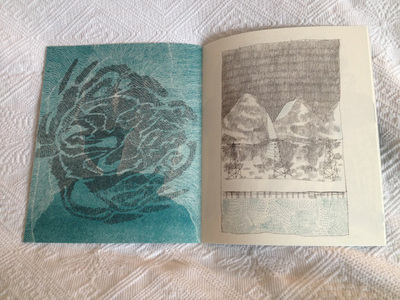

Dreams, before Freud, were always associated with reaching beyond: somewhere out of this world, greater than ourselves. The Underworld was a place, actual as well as symbolic, related to this world, but also distinct from it. It was certainly taken to mean much more than the unconscious. Most of us would readily see a connection between the dream and the underworld, but because they are broad terms, it is less easy to explore what that connection might be. That is the territory of this show. It reveals a landscape that is both familiar and unfamiliar, one that asks us to be prepared to set aside what we think we know in favour of larger truths that may disturb our ideas of order. In the light of this simultaneous strangeness and naturalness, both inside and beyond, this piece of text was composed in ways inspired by the Surrealists. Their idea was to get beyond ordinary ways of thinking, to ‘send the mind on holiday’ (in André Breton’s words), and allow chance and a more communal way of making art to emerge. One way of doing this was through automatic writing and, famously, the ‘cadavre exquis’ or exquisite corpse. Not that this show is communal in that sense, or Surrealist. But it reaches to areas of experience that are much more to do with the collective unconscious than the individual. In terms of language, it allows words and grammar themselves greater prominence than one person’s way of using them (‘langue’ rather than ‘parole’ for the linguists). How we went about trying to reach this through writing about the works in the exhibition is set out at the end of this text. What follows now is the result, a mix of the words of the three of us, put together by Penny, who devised the whole crazy idea in the first place. We hope you enjoy it, and that it complements your responses to the art works. Please read the following as if it applied equally to both the artists’ work, rather than expressing their individual beliefs. It was produced to a greater or lesser degree out of the force-field set up between the works. Keywords: Dynamic energetic, supernatural Primitive magical, ritual Wonderful awe, wonder Connected sun and moon, oscillation, wild, Raw, Land, enchanted, connection cave, sea cave, ancient magic/ancient/divine, art, savage shiver, bloodlines/survival, ancestor. I feel we all have an internal mythology and I explore methods to connect to interior worlds. That’s where mythology lives. On balance, if the void can have narrative qualities, they must be defined by the human mind or natural processes. I use colour emotionally and all at once when extremely happy. This is a response to the wilderness, as ideas emerge when in it. The titles of work are part illumination, part ambiguity – a map without a destination. Drawings are, too. Ideas constellate depending on the context but generally words and images work together in an oscillation, not to clearly define. So there is a restriction of a sort, but ever changing. Ambiguity isn’t an obstacle to telling a story; everything has a narrative when we look for it. Ambiguity allows it to be personal. I don’t feel I relate to any part of the contemporary ‘art scene’, or, if I do, it is an uncomfortable relationship. Same goes for religion. I think of my own work as artefacts or talismans before I think of them as sculptures. The word sculpture doesn’t quite define what I set out to do (though it is, of course, a useful term of reference). There is, I feel, a resurrective, atoning or ceremonial aspect to my work, especially given the fact that I use animal remains and natural materials. Even the act of sculpting is only a small part of the process, to the point that it is possible to make something with very little of that technique, there being a world of experience to draw from. I don’t know what ‘collaborative’ means. My gut reaction to the word ‘abstraction is one of relief. The ritualistic aspect of art does this, too. Scale doesn’t matter at all. Nor does permanence. What interests me most in the art of the past is the primitive, when art was magic. That’s what I hope the audience might sense in my work. I think my use of colour is a reaction to its absence in my earlier work and a reliance on a very limited palette. It is also perhaps the only instance where I have been moved to change ever so slightly an aspect of my practice in response to outside opinion and to make the work slightly more commercially viable. For people, naturally, tend to have a positive response to colour. Having said that, the only colour that interests me is what I see in nature, and any attempt to replicate this in a work is doomed. The original colours that go into a piece (that which is brought in from the land - leaves, wood, animal remains) achieve a kind of unity and essence through amalgamation. The fact that this tends towards dark and black gives me a sense of gratification - I lean naturally towards the void, decay, death and reanimation, the esoteric, the earth and the quality of the archaic or disinterred, physically or mentally, that a near absence of colour can achieve. So my relationship with colour in art derives very clearly from the natural world. Its importance doesn’t quite come from the same aesthetic considerations that concern many artists. Note on the method of composition Penny compiled a list of words from looking at the work Lucy and Jim planned to show. This formed the basis for questions to each of them. Then the writer made two lists by selecting from the questions at random - literally out of a hat. The artists did not know who the questions were originally intended for. Neither of them knew what the other had been asked, or had said, until afterwards. But once they had read each other’s replies, the writer asked each artist to re-invent the questions they thought the other had been asked. The writer then made a draft, which included new thoughts and previously unconscious responses/comparisons/associations about the works that came up as a result of the process. Only then did the artists find out whether they got ‘their’ questions. The artists’ comments on the draft were incorporated into the final version, which you have in your hand. Professor Penny Florence PhD The Slade School of Fine Art UCL

|